Introduction

Over the last decades, student immigrants have been encouraged to fulfill Canada’s specific labor market demands. My paper will explore the social impacts of student immigrants on Canadian society. I discuss Canada’s historical trends and policies regarding international students compared to other immigrant categories. Particularly, I examine the combination of the Post-Graduate Work Permit (PGWP) and the Express Entry (EE), which facilitates student immigration in Canada and thus serves as a pre-context for my subsequent discussion of the social impacts. I first examine the diversity of international students, both demographically and culturally. Then, I articulate how diversified student bodies necessitate the progress of social inclusivity and justice, exemplified by student activism seen at the University of British Columbia (UBC). My final section focuses on the global connections that student immigrants possess. Their global connections, I argue, lead to a more internationalized landscape of knowledge production while benefiting research practices in Canadian post-secondary institutions. Manifesting in their interpersonal connections, intercultural and multilinguistic skills, student immigrants’ global connections also help build Canada’s increasingly transnational business climate and inter-governmental relation-building. Overall, I contend that student immigrants form a unique spectrum of diversity, which requires more individualized delivery of public goods. Therefore, Canadian society witnessed rising student activism, contributing to social inclusivity and justice, the internationalization of academia, transnationalization of business and politics, thanks to student immigrants’ global connections.

The Review of Canada’s Migratory Trends and Policies

In the first section, I briefly review migratory trends and policies, both historical and contemporary ones of Canada, which always represents itself as a “cultural mosaic.” The most recent Canada census in 2021 shows that immigrants make up 23% of the Canadian population, 56% of whom are third or more generation population (Statistique Canada, 2022). The paper will also discuss other migratory categories such as refugee resettlement, and labor migration, which can serve as a comparative analysis with international students’ discussion.

Historical Review of Migration in Canada

The earliest phases of migration in Canada began in the era of settler colonialism, when European settlers undertook the colonization of territories inhabited by First Nations and Métis peoples, leading to their displacement and significant disruptions to their ways of life. This period, predominantly spanning the 17th and 18th centuries, saw substantial influxes of European settlers, including the British, French, Irish, and others, driven by motives ranging from economic opportunities to religious freedom. The 19th century witnessed significant waves of immigration to Canada, driven by factors such as economic opportunities, political unrest, and religious persecution in Europe. Following the establishment of the settler state in 1867, Canada’s approach to immigration began to take shape within the framework of its constitution. The British North America Act of 1867, which formed the basis of Canada’s constitution, granted the federal government control over immigration and naturalization. This constitutional provision empowered the government to establish immigration policies and regulations that would shape the country’s demographic composition. Two years later, the Immigration Act of 1869 marked one of the earliest formal attempts by the Canadian government to regulate immigration. It aimed to address concerns about the quality and quantity of immigrants entering the country, introducing provisions for health examinations and immigration controls.

In the late 19th Century, Canada employed human-capital immigration selection criteria, favoring immigrants with desired skills. A notable example of this era is the direct recruitment of Chinese temporary foreign workers (TFWs) by the Canada Pacific Railway in the 1880s. Approximately 15,000 Chinese laborers were enlisted to construct the Canadian Pacific Railway under arduous conditions and for meager wages, with at least 600 fatalities recorded among the workers (Lavallé, 2008). However, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 (also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act) imposed a head tax on Chinese immigrants entering Canada, aimed at discouraging Chinese immigration. It was followed by subsequent laws further restricting Chinese immigration, reflecting anti-Chinese sentiments prevailing at the time. Similarly, the Continuous Journey Regulation of 1908 was designed to restrict immigration, particularly from South Asia. The legislation requires immigrants to arrive in Canada via a continuous journey from their country of origin, thus targeting immigrants from India, as there were no direct shipping routes available from India to Canada at the time. In short, the early history of migration in Canada illustrates the complex and often exploitative nature. It laid the groundwork for subsequent immigration policies and practices, shaping the demographic and socio-economic landscape of the country. (Akbari & MacDonald, 2014; Brunner, 2017)

Contemporary Migratory Policies and Practices

Since the 20th Century, the Canadian government has been continuing its immigration based on the human-capital selection model while allowing migration from a wider range of origins. Canada in World War II, witnessed a significant trend of refugee resettlement, as the country accepted refugees and asylum seekers from war-torn countries such as Vietnam, Bosnia, and Syria. Meanwhile, the state actively engaged in nation-building through the establishment of its language and institutions. The 1960s marked a transiting moment for popular migration destinations such as Canada, as they began to attract immigrants from a broader range of countries of origin (Czaika & Reinprecht, 2022). During the 1960s, Canada experienced a significant decline in its fertility rate, promoting concerns about the aging population. Consequently, the Canadian government introduced a series of migratory policies aimed at attracting immigrants of working age, such as the introduction of a points-based immigration system in 1967 and the establishment of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) in 1973. The Points System assessed immigrants based on factors such as education, language proficiency, work experience, and adaptability. Without solely assessing immigrants based on their country of origin or ethnicity, the Point System marked a significant shift in Canada’s previous discriminatory immigration policy.

The globalization of the economy and trade compelled Canada’s selection criteria to shift from the human-capital model to demand-driven immigrant selection approaches (Brunner, 2016). The trend could be particularly seen in the regionalization of migration policies. In the late 20th century, provinces in Canada demanded more regional flexibility in migration, as labor market demands and demographic challenges varied from province to province. In 1998, the first Provincial Nominee Programs (PNP) were launched in Manitoba. It allowed the province to nominate individuals who met its economic and demographic needs for permanent residency in Canada, thus satisfying specific provincial needs from migration. Following Manitoba’s lead, other provinces and territories began developing their own PNPs, each tailored to their unique economic and social contexts. By the early 2000s, several provinces, besides Quebec, had implemented their nominee programs. More agreements between the federal government and individual provinces or territories expanded the PNP framework to include all provinces and territories, recognizing the benefits of regional autonomy in immigration selection. The flexibility that regionalization of migration grants Canadian provinces, shifts the process of immigrant selection in Canada into a more demand-driven direction. (Akbari & MacDonald, 2014; Brunner, 2017)

Students in Migration Practices

International students, seen as a future workforce and “creative class” communities with high potential, are therefore gaining more government attention. The notion of “creative class,” was brought up by Richard Florida, an urban studies theorist focusing on social and economic theory. In his book The Rise of the Creative Class, Florida defines “creative class” as “people in design, education, arts, music, entertainment” “and small business too” who “create new ideas, new technology and/or creative content” (2012, p. 7) and therefore plays a significant role in shaping the socioeconomic dynamics of global cities.

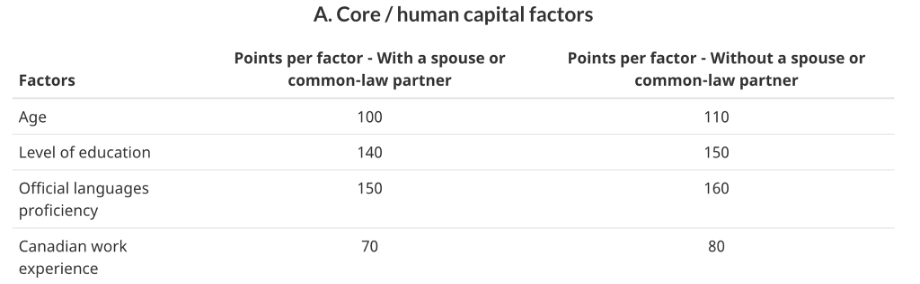

To a large extent, the notion of “creative class” aligns with the high-skilled immigrant worker whom the Government of Canada has been encouraging to migrate through programs such as Post-Graduation Work Permits (PGWP) and Express Entry (EE). Established in 2015, the Express Entry Program (EE) targets specific labor market needs and particularly attracts high-skilled workers. The program is tailored for graduated international students, who possess “advanced English language proficiency, fully recognized qualifications, locally relevant professional training, and a high level of acculturation” (Hawthorne, 2005, p. 686). The EE program employs a “Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS) Criteria,” which demands migrant candidates from mainly three perspectives: age, language skills, and skill or working experience. As articulated earlier, graduated international students are preferred by Canadian employers due to their “advanced English language proficiency, fully recognized qualifications, locally relevant professional training, and a high level of acculturation” (Hawthorne, 2005, p. 686). Moreover, the Government of Canada also takes the creative class’ high level of mobility into policymaking. The creative class tends to be more mobile, primarily because most are young and single (Florida, 2012). Therefore, higher points for candidates “without a spouse or common-law partner” functions, in particular, to retain single creative class members to some degree (see Appendix A).

Therefore, student immigrants require working experience to land a Canadian Permanent Residence. To facilitate this effort, the Canadian government implements the Post-Graduate Work Permit Program (PGWP) to target and retain international students upon completion of their degrees. Through PGWP, international students are eligible to apply for a work permit for a duration of up to three years after completing their studies. In 2023, Sean Fraser, Minister of Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) stated Canada’s ambition to continue to encourage migration:

In the 2023–2025 Immigration Levels Plan, Canada aims to welcome from 410,000 to 505,000 new permanent residents in 2023, from 430,000 to 542,500 in 2024, and from 442,500 to 550,000 in 2025. […] continuing to welcome newcomers through temporary worker and student streams. Both temporary workers and international students have the opportunity to remain in Canada as permanent residents if they wish to make their new home here. (Mallees, 2024)

The combination of these two programs is particularly targeted at the potential of international students to become a future workforce. According to the CBIE International Student Survey (2021), 72.5% of international students plan to apply for a post-graduate work permit (PGWP) after graduation. Meanwhile, over 60% of international students plan to apply for permanent residence in Canada. Therefore, Canada’s migration policies and trends, particularly those targeting student migration, form crucial prerequisites and contextual frameworks within which the impacts of student migration unfold. (International Students in Canada Infographic, 2023)

Interconnected Social Impact of Student Migration

In the following sections of my paper, I focus on discussing the social impacts of student immigrants in Canada, which encompasses diversity in educational institutions; increasing youth activism, social inclusivity, and justice; and finally, global connections. Specifically, I articulate how these categories of social impacts are interconnected, while jointly shaping the landscape of student migration in Canada.

Diversity

Over the past two decades, Canada’s migration policies, such as the PGWP program, have significantly diversified the patterns of student populations, leading to an increase in both the number of students and their origins. According to recent data from the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE), the number of international students in Canada surged by 29% from 2022 to the end of 2023, surpassing 1 million in total. This influx encompasses diverse demographic backgrounds, with a predominant representation from Asia (International Students in Canada Infographic, 2023).

Even though Canada has a long migration history, “cultural mosaic” did not become its national representation until the contemporary era of Canadian migration practices. Multiculturalism was integrated into the Canadian constitution in 1971, marked by the implementation of the Multiculturalism Policy. This policy aimed to promote social cohesion and inclusion by recognizing the contributions of diverse ethnic and cultural groups to Canadian society. Since then, Canada officially started to recognize and celebrate the cultural diversity of its population. For Canada, cultural diversity is not just a byproduct of migration but a reflection of the country’s overall migration policies and programs. Beyond demographic diversity, international student immigrants bring a wealth of cultural diversity. At the University of British Columbia (UBC), for example, there are over 650 student clubs and societies, with more than a quarter dedicated to showcasing the regional, social, and cultural diversity of specific student immigrant communities. These associations serve as platforms for fostering cultural exchange, understanding, and integration. Many student associations, such as the Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA), Hong Kong Students’ Association (HSA), and Bangladeshi Students’ Association (BSA), are founded based on shared identities, promoting social cohesion and integration within the broader student community. The diversity brought by international students greatly enriches UBC’s cultural landscape. For instance, during significant Chinese festivals like the Lunar New Year, immigrant student communities organize elaborate celebrations featuring traditional performances, culinary delights, and cultural exhibitions. These events not only showcase the richness of Chinese heritage but also serve as platforms for intercultural dialogue, inviting Canadians of all backgrounds to participate and learn. Therefore, the plethora of traditions, arts, and cuisines brought by student immigrants, fosters a deeper understanding and appreciation of the culture of their home country among Canadian communities.

Youth Activism, Social Inclusivity, and Social Justice

As discussed in the last section, the diversity of student migration represents a fraction of the Canadian “cultural mosaic” facilitated by decades of migration policies. However, international student-specific diversity could be more vigorous and crucial to Canadian society in ways that contribute to youth activism, social inclusivity, and justice.

In addition to fostering cultural understanding, increasing student immigration contributes to a more inclusive Canadian society. With a diverse student body, educational institutions are compelled to tailor their support services to meet individual needs. As noted by Michalski et al. (2017), many post-secondary institutions in Canada have witnessed a surge in one-to-one support services, including accessibility, counseling, and learning strategies. This shift reflects a commitment to accommodating the diverse needs of international students, promoting their integration, and fostering social inclusivity within Canadian educational environments. Thus, increasing student migration propels institutions to consider the diversity of bodies, contributing to a more inclusive landscape for immigrants through a bottom-up approach.

Moreover, the diversity brought by student migration fuels youth activism and, in a bottom-up way, contributes to social justice initiatives. Immigrant students are often likened to “canaries in the mine shaft,” serving as early indicators of systemic societal injustice. This analogy highlights their role in confronting and exposing underlying issues, which the student movements at UBC can exemplify. Political conversations in the United States during the late 40s began to influence Canadian activism, leading to the establishment of organizations like the Canadian League for the Advancement of Colored People, which advocated for the professional success of Black job seekers beginning in 1947 and 1948. Meanwhile, the enrolment of international students increased. Despite limited demographic data until 2020, UBC saw a drastic increase in enrollment over the following decades, particularly among marginalized populations and international students. Consequently, more groups have been founded for specific demographics and communities given more diversified backgrounds of student stakeholders.

This trend and the analogy of “mine shaft canaries” can be exemplified by the housing challenges faced by international students at UBC. In Vancouver, a global city that has been confronting housing speculation and challenges due to its increasing population, international students are particularly vulnerable for intersectional reasons. While bearing higher tuition, international students enjoy less student services and aid than domestic. At UBC, for instance, international students bear tuition fees nearly ten times higher than domestic students, while do not have access to any financial bursary. Financial aid and bursary are available for “Canadian citizens or permanent residents” only. To secure on-campus housing whose prices are below market average, it is common for UBC students to be waitlisted for 2 to 3 years. Thus international students initiate ongoing student-led movements, such as the housing4right beginning in September 2023. These student activism movements underscore the pressing need for improved student housing solutions, thus urging the institution to come up with solutions for housing justice. In response, UBC has partnered with private property development firms, resulting in year-round construction sites dedicated to forthcoming student accommodation. There have been 2 new buildings of Brock Commons residences constructed and furnished from the academic year of 2023 to 2024, accommodating over 600 more students (Brock Commons Tallwood House, 2022). However, these solutions are not immediate fixes to the housing challenges faced by student immigrants. Nevertheless, student movements, largely fueled by international students who confront more injustice, continue to challenge institutions for reform toward a more just landscape. Their activism catalyzes change and pushes for tangible solutions to address systemic issues within Canadian higher education.

Global connections

In the final section, I discuss how student immigrants in Canada demonstrate their diverse global connections, within higher education institutions, business sectors, and governmental sections. I will first articulate how student immigrants could facilitate“internationalization” in Canadian higher education institutions. Then, I will zoom in on their social impact in the field of business, examining how they function as the future “creative class” contributing to the transnational business climate, interpersonally, linguistically, and interculturally in Canada.

Internationalization of Academia

To begin with, the global connections of student migrants could facilitate the internationalization of academic spheres, particularly higher education institutions in Canada. As defined by Knight (2014), the term “internationalization” refers to “the process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions or delivery of post-secondary education” (p. 11). Framed in education discourse, it encompasses a series of international activities, such as the academic mobility of students and faculty; international linkages and partnerships; and new international academic programs and research initiatives (Knight, 2004).

Familiar with the context of their home country, student immigrants could build upon the knowledge production in the institutions of the country they migrate to. I use my personal experience as a student immigrant from Asia to Canada as an example. By engaging in class discussions that are mostly European or North American-based, I always bring an Asian-specific perspective that “sounds interesting” to my classmates. In one of my courses regarding transnational politics of reproduction, my classmates were actively discussing the morality of abortion given the baby’s abnormality, such as Down syndrome. They were debating whether, as the parents’ decision to terminate the pregnancy due to the baby’s inability deprives its right to be alive, the government could intervene to eliminate or reinforce ableism. While my classmates were occupied discussing scenarios based on both sides of the debate, I raised my hand, contributing a new argument, arguing that whether the state intervenes in genetic testing or not will reflect the state’s will to control its population. I supported my opinion with the relevant contexts in China, comparing policies of genetic testing and abortion in Mainland China and Hong Kong. I articulated that, testing of a baby’s gender is not allowed in Mainland China, which reflects on the Chinese patriarchal family tradition that prefers boys so much to girls that, if the baby is tested being a girl, the mother could be coerced to terminate her pregnancy by elder generations from the extended families. Meanwhile, abortion is allowed in the mainland, which, however, is not for the sake of “women’s right to bodies” but largely due to China’s overpopulation concern. After class, a European student came to me and complimented me, “Hey, I like your point about China’s allowance for abortion. It’s quite new and interesting to me.” The academic discourse in educational institutions in the Global North tends to be primarily dominated by Eurocentric and North American focus. However, education should “depart from ‘home’ and encounter otherness, separated from the familiar and determined, becoming the wanderer, the nomadic consciousness, opening to multiplicity” (Serres, 1997, as cited in Guo et al., 2010, p. 85). It occurred to me that distinct geographies of student immigrants could be more invaluable in contributing to the internationalization of knowledge production in the countries they migrate to.

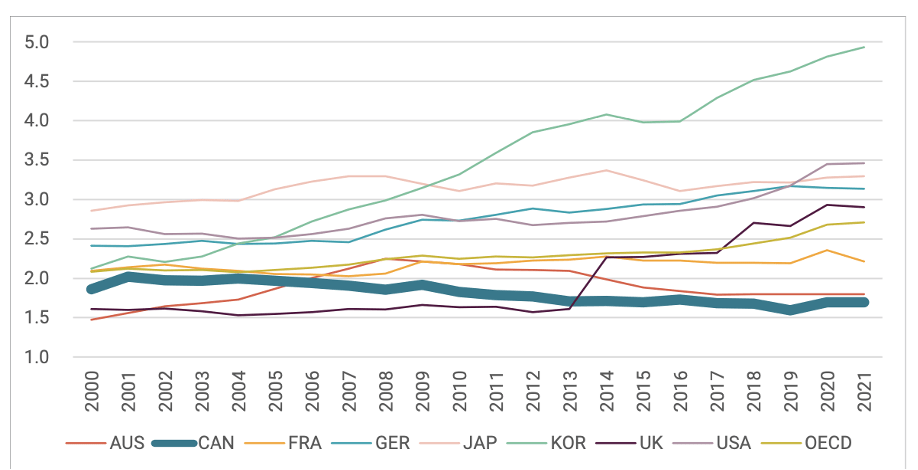

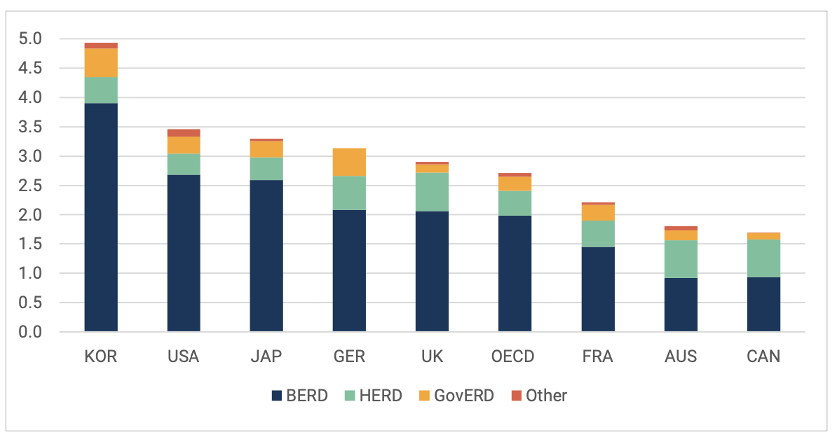

Besides their familiarity with the geographical context of their home country, student immigrants in Canada also internationalize academic research. Specifically, I argue that student migration may have increased the utility of the Canadian state’s R&D spending in higher educational institutions. As indicated in The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada (the “Education” from now on, Usher & Balfour, 2023), Canada has never been a global leader in research and development (R&D), which can be seen from its under-investment in R&D when compared to its global peers. As shown in Research and Development Spending as a Percentage of GDP (see Appendix B-1), Canada has historically been among the lowest spenders in terms of R&D among selected OECD countries. Recent years have even witnessed that Canada goes against the OECD-wide trend of rising R&D expenditures. However, what is notable here is that, in contrast to overall R&D spending, Canada ranks favorably among OECD countries regarding government expenditures on R&D in the higher education sector (HERD). As shown in Figure B-2 (see Appendix B), which contrasts the overall size and composition of R&D expenditure in Canada to other selected OECD countries, Canada’s HERD spending makes up a high share of its overall R&D expenditure. As suggested in Education (2023), one possible explanation for Canada’s HERD performance being above the OECD average is the degree of its transnational scientist collaboration, where student migration plays a vital role. In 2020, over 58% of scientific publications with a Canadian author have an international co-author. In many departments of Canadian higher education institutions, transnational geographical perspectives have been valued or even prioritized when conducting research. At UBC Geography, one of the top geography departments in the world, for instance, global perspectives and approaches are emphasized in its program descriptions. The presence of “human” “humanity” “transnational” and the usage of “social” “economic” and “cultural” in a global context are frequently seen while going through the official website of UBC Geography. Thus, the internationality of academics has been incorporated and highlighted in the curriculum design.

Transnationalization of Business and Inter-governmental Relations

The global connections that student immigrants bring along could also manifest their social impact in business sectors, as students have the full potential to be the future “creative class” and future high-skilled migrant workers desired by the state. Transiting from the academic sphere to the workforce, students often bring a wealth of knowledge and skills that can drive forward the creation of new ideas, technologies, and creative content. Being trained in the Canadian educational system, international students’ familiarity with Canadian society, their linguistic skills, and their body of knowledge save employers from preliminary labor training. Therefore, student immigrants tend to be favored by Canadian employers, either in the business or governmental sectors, which is embodied in the combining implementation of PGWP and EE programs. While the Government of Canada designs its selection criteria primarily based on immigrants’ economic value, which many scholars and policymakers have studied, the social impacts of student migration remain less frequently discussed in the current state of knowledge. Thus, my following discussion focuses on the social impacts of student migration in the field of business. In particular, I examine how they function as the future “creative class” and high-skilled workers contributing to Canada’s transnational business climate, interpersonally, linguistically, and interculturally.

Firstly, the global connections of international students set their social impacts apart from those of domestic students in terms of the interpersonal relationships they possess transnationally. Many international students maintain strong connections with their home countries, such as professional networks, and family ties. These interpersonal connections can indeed serve as valuable assets for Canadian businesses looking to expand into global markets, thus forming a transnational business climate. For example, imagine a Chinese international student studying business in Canada who maintains close relationships with industry professionals and entrepreneurs back home. If a Canadian company seeks to enter the Chinese market, it could leverage the student’s network to establish partnerships, gain market insights, and navigate cultural nuances. Similarly, international students from countries like India, Brazil, or Nigeria may provide invaluable assistance to Canadian businesses looking to tap into emerging markets or strengthen existing international ties.

Global connections of student immigrants encompass more than just interpersonal connections or family ties between their home country and country of residence. It also refers to the multilingual and intercultural ability of a student migrant, and their deeper understanding of the home country in terms of its social, cultural, and political context. Their unique position as bridges between different cultures, politics, and markets has the potential to offer invaluable insights and opportunities for cross-cultural collaborations or transnational cooperations (TNCs), which are increasingly essential in today’s interconnected world. For instance, Vancouver has witnessed a significant presence of three of the world’s top 10 tech companies by market capitalization: Microsoft, Amazon, and Samsung. A great number of TNCs regard Vancouver as home, largely thanks to its large body of diversified student population in the University of British Columbia (UBC, a home to 72,585 students), Simon Fraser University (SFU), and so on. Besides transnational partnerships that student immigrants facilitate TNCs based in Canada to establish, their familiarity with the socioeconomic and cultural contexts of their home country could also be utilized for inter-governmental relation-building. Karla, an international student from Poland who studies international relations at UBC, was hired by the government of Canada to work as a policy analyst and consultant on the bilateral relations between Canada and Poland. Her body of knowledge in international relations, bilingual linguistic skills (Polish and English), and intercultural understanding of both countries equip her with assets to perfectly match the job. Therefore, student immigrants’ global connections are embodied in and utilized by both transnational sectors of business and politics in Canada, thanks to the linguistic, intercultural, and intellectual abilities of international students.

In short, migration impacts embody the states’ migration policies. Despite being categorized, these three kinds of impacts take place in the political context of migration trends discussed previously and are therefore interconnected. Canada’s decades of encouraging migration policies and practices diversify the demographic and cultural backgrounds of student immigrants. Consequently, a diversified student body requests institutions and Canadian society, in general, to deliver more individualized public goods to the population. For this trend, more student activism movements have been witnessed in Canada and a higher level of social inclusivity and justice are in the course of being reached. The diversity of student migration also benefits the field of academia, business, and politics in Canada, thanks to the global connections that student immigrants possess, which not only manifest in their interpersonal connections but also their intercultural and multi-linguistic abilities.

Conclusion

In conclusion, my paper examines the social impacts of student migration in Canada. As migration impacts are, to some extent, a manifestation of migratory policies, my paper briefly outlines Canadian migratory trends and policies. Despite Canada’s long history of being a migration country, student migration didn’t gain a significant presence until Canada’s contemporary migration practices. Migration programs such as EE and PGWP, utilize student potential as future creative class and high-skilled immigrants and largely facilitate student immigration in Canada. The second section of my paper discusses the social impacts of student migration, including three aspects: demographic and cultural diversity, consequent student activism, and social inclusivity; and finally, global connections in the field of academia, business, politics, given student immigrants’ interpersonal, intellectual and interpersonal assets. Canada’s decades of migratory policies and trends have led to a body of more diversified international students demographically and culturally. Additionally, a diverse student body compels educational institutions and the general society to tailor their support services to meet individual needs, as more youth activism movements are fuelled by student immigrants and contribute to social justice initiatives. Regarding global connections in academia, student immigrants produce distinct knowledge with unique contexts and thus internationalize research practices in Canada’s higher-education institutions. The global connections of student immigrants also lead to a more transnational business climate in Canada, while facilitating inter-governmental relation-building. Overall, these three categories of social impacts are interconnected in ways that the diversity of student bodies requires more individualized delivery of public goods, which therefore contributes to social inclusivity and justice through rising student activism; meanwhile, it leads to the utilization of student immigrants’ global connections.

References

Akbari, A. H., & MacDonald, M. (2014). Immigration Policy in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: An Overview of Recent Trends. International Migration Review, 48(3), 801–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12128

Brock Commons Tallwood House: Demonstrating the viability of mass wood structures. (2022). https://www.thinkwood.com/construction-projects/brock-commons-tallwood-house

Brunner, L. R. (2017). Higher educational institutions as emerging immigrant selection actors: A history of British Columbia’s retention of international graduates, 2001–2016. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 1(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2016.1243016

Czaika, M., & Reinprecht, C. (2022). Migration Drivers: Why Do People Migrate? In P. Scholten (Ed.), Introduction to Migration Studies (pp. 49–82). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92377-8_3

Florida, R. (2012). The Rise of the Creative Class (Revisited). Basic Books.

Guo, S., Schugurensky, D., Hall, B., Rocco, T., & Fenwick, T. (2010). Connected Understanding: Internationalization of Adult Education in Canada and Beyond. Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education, 23(1), 73–89.

Hawthorne, L. (2005). “Picking Winners”: The Recent Transformation of Australia’s Skilled Migration Policy. International Migration Review, 39(3), 663–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2005.tb00284.x

International Students in Canada Infographic. (2023). https://cbie.ca/infographic/

Knight, J. (2004). Internationalization Remodeled: Definition, Approaches, and Rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315303260832

Knight, J. (2014). Is Internationalisation of Higher Education Having an Identity Crisis? In A. Maldonado-Maldonado & R. M. Bassett (Eds.), The Forefront of International Higher Education: A Festschrift in Honor of Philip G. Altbach (pp. 75–87). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7085-0_5

Lavallé, O. (2008). Canadian Pacific Railway. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-pacific-railway

Mallees, Nojoud Al. “Minister Was Warned about Possible Negative Impacts of Lifting International Student Work Limit | CBC News.” CBC, 13 Feb. 2024, https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/international-student-work-hours-1.7113381.

Michalski, J. H., Cunningham, T., & Henry, J. (2017). The Diversity Challenge for Higher Education in Canada: The Prospects and Challenges of Increased Access and Student Success. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, 39, 66–89.

Statistique Canada. (2022). Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population [dataset]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Usher, A., & Balfour, J. (2023). The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada, 2023.

Appendix A

(Figure A-1, Core/human capital factors, CRS Criteria, Government of Canada, n.d.)

Appendix B

(Figure B-1, 2000-2021 Trend of R&D Spending as a Percentage of GDP, Selected OECD countries, as cited in Usher & Balfour, 2023, p. 68)

(Figure B-2, R&D Spending by Sector, as a Percentage of GDP, 2021, Selected OECD countries, as cited in Usher & Balfour, 2023, p. 69)

Leave a comment